A study appearing in the journal found that most nutritional supplement shops would advise a 15-year-old boy to take creatine supplements to build muscle, despite an American Academy of Pediatrics recommendation against the practice. In this analysis, ��������app clinical reviewer F. Perry Wilson, MD examines the data and assesses "what's the deal with creatine?"

The American Academy of Pediatrics specifically recommends against the use of a particular substance in adolescents. But it is being sold to them, perfectly legally, by nonmedically trained personnel. Are you outraged? Well – the substance is creatine and I'm not sure I can get too exercised about this one.

We're talking today about this article appearing in the journal Pediatrics:

The question at hand – would retailers in vitamin and supplement shops recommend creatine or testosterone boosting agents to a purported 15-year-old boy on the phone asking about ways to bulk up for football sophomore year?

The results in a second – but first: What's the deal with creatine?

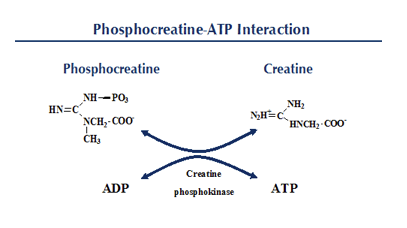

The idea behind creatine as a muscle-building supplement comes from the fact that creatine phosphate is the major energy storehouse in muscle.

That phosphate on the end regenerates ATP from ADP, allowing your muscles to continually exert themselves. Without creatine phosphate, your muscles would "fail" after around 5-10 seconds of isometric tension.

And that's why creatine supplements are big players in the 30 billion dollar nutritional supplement market.

But what does the data show? Can creatine increase performance?

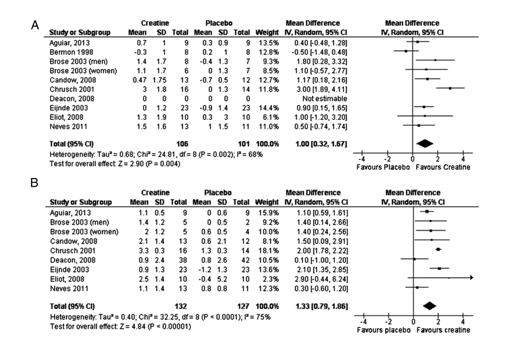

Well – maybe, a bit. There's a lot of research out there, but the gist is that creatine supplementation may help with brief, power-driven activity (like resistance training). There seems to be no real effect on cardio or endurance training. Here are results from a nice meta-analysis examining creatine versus placebo in older adults and basically showing a modest benefit in terms of body composition.

Unfortunately, we don't have much research in adolescents. And creatine supplementation is not without risks – primarily GI distress, but some have noted the potential for both liver and kidney toxicity. It's likely the risk profile in adolescents is unique as well.

Existing research suggests that 30% of high school boys use creatine. This seems high to me, but then again, I was a math and debate team member in high school and may not have had quite the same peer pressure to bulk up.

OK, back to the study.

The researchers called 244 supplement shops across the country and asked what they would recommend for this 15-year old male.

As you can see, about 40% of the time he was told to take creatine without any prompting. Another 30% of the time, when he asked about creatine, the individual on the phone would agree it was a good idea.

Thirty percent of the individuals recommended against. That's the official position of the American Academy of Pediatrics.

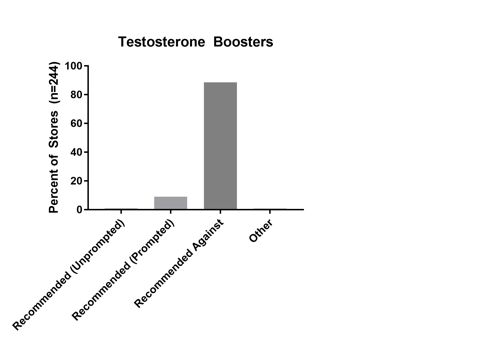

The results for testosterone boosting agents – an area of the supplement world with even less compelling data than creatine – weren't too bad:

Almost everyone recommended against these agents for the 15-year old boy.

Some states have attempted to pass laws prohibiting the sale of muscle-building supplements to minors. To date, no such laws are on the books. That's probably OK. I actually wonder if diverting some kid's tendency to look for a quick fix to muscle-building into the relatively-safe area of creatine use is better than putting all muscle builders, from creatine to anabolic steroids, into the do-not-touch category.

But it's clear, at least, that pediatricians and parents should be asking high school boys about this. They don't like talking much, but hey, stay strong.